Drone, Inc. - A. Full Motion Video

The two most important, and quite different, functions of military drones are keeping watch over troops and identifying potential enemies. While troops can and want to identify themselves to drone personnel, hostile forces do their best to camouflage their movements and blend into the background and civilian populations.

Imagery analysts, who act as guardian angels to fellow soldiers under attack, report immense job satisfaction. “It’s not just blips on the screen and video games,” Amy, a National Guard civilian who works in drone surveillance at Joint Base Langley-Eustis, told the Virginian Pilot newspaper during a March 2015 day tour for the local media. “These are real people, and they have families and lives and, in that moment, you are the person ... that is making sure they are protected.”22

Their role is especially gratifying in times of conflict. “If there is an op going on, the guys on the ground can’t see over a wall, they can’t see on the other side of a building or a hedgerow,” Caleb, an Air Force lieutenant told the same newspaper. “We can say, ‘Hey, you got three dudes on the other side of this wall right over here, so watch for them’... or ‘We just saw a child come out of this building, there’s a woman there, we can’t strike this. Call off the strike right now.’“

Yet even on these occasions, the cameras that military drones carry are surprisingly limited. In April 2011, a Predator was assigned to support Marines involved in a ground battle with the Taliban in Afghanistan. The commanders made a judgment call based on muzzle flashes and called in a Hellfire missile strike, only to discover that they had targeted and killed Jeremy Smith and Benjamin Rast, two U.S. soldiers in full battle uniform.23

Later Jerry Smith, Jeremy’s father, was shown video of the strike. All he could see, he told the Los Angeles Times, was “three blobs in really dark shadows. You couldn’t even tell they were human beings—just blobs.” It was impossible, he noted, to identify their uniforms or weapons or differentiate U.S. soldiers from Afghans.

Indeed, Predator operators on the U.S.-Mexico border say they have to rely on direct radio contact to overcome similar limitations. “We can see Border Patrol, but not their uniforms, and so we can communicate with them and say, ‘Wave your arms,’ and that way we can distinguish between our guys and the bad guys,” Lothar Eckardt, director of the Department of Homeland Security’s National Air Security Operations Center in Corpus Christi, Texas, told the Washington Post.24

Drones are often touted as able to read a license plate from two miles away, but operators say this is rarely true. “The video provided by a drone is not usually clear enough to detect someone carrying a weapon, even on a crystal-clear day with limited cloud and perfect light,” Heather Linebaugh, a former Air Force imagery analyst, wrote in the Guardian newspaper in 2013.25

“This makes it incredibly difficult for the best analysts to identify if someone has weapons for sure. One example comes to mind: The feed is so pixelated, what if it’s a shovel, and not a weapon?”

Usually, the best an analyst can hope for is to follow one group of people, and distinguish men from women or adults from children, but even that can be difficult, as the Uruzgan example (see box) shows. In Central Asia and the Middle East where most men wear very similar clothes and have the same color hair and skin,26 identifying an individual from a Predator at 10,000 feet is essentially impossible. Facial recognition is also impossible without a camera located at eye level.27

Using video for observation has also been found to increase human error. A Grumman Aerospace study conducted by Pierre Sprey in the 1960s, found that observers watching aerial video tend to identify as many as five times more false objects as observers watching with the naked eye. 28

28

So what cameras do Predators and Reapers carry, and why don’t they provide better imagery?

The Cameras

The system of choice for over a decade has been Raytheon’s MTS-A ball, which has two video cameras installed as part of the standard package. One is a color camera mounted on the nose to help the pilot steer; the second is a RS-170 Versatron camera for looking down at subjects. 29

29

The Versatron transmits pre-digital TV-standard quality: 512x480 pixel images. It is good enough when filming close up, but from a height of 10,000 feet, even with image intensification technology, the average person is reduced to a splotch. Since the camera has a 16-160mm zoom lens as well as a 955mm spotter lens, a camera operator can zoom in and read to the detail of a license plate, but not much else at the same time, because of the “soda straw “restriction of the field of view. For most of the last 20 years, these older cameras were standard. 30 The Air Force has now mostly replaced the Raytheon MTS-A ball with the more advanced MTS-B or the heavier Wescam MX series made by L-3 Communications of New York, which carries a high definition camera and is used on piloted surveillance aircraft.31

30 The Air Force has now mostly replaced the Raytheon MTS-A ball with the more advanced MTS-B or the heavier Wescam MX series made by L-3 Communications of New York, which carries a high definition camera and is used on piloted surveillance aircraft.31

Video Quality

Drone Strike Kills 23 after Video Feed Fails to Identify Women and Children A convoy of three vehicles was winding its way through the empty back roads of rural Uruzgan Province, Afghanistan, early on a Sunday morning in February 2010, when U.S. forces fired a series of missiles at it. Between 15 and 23 people were killed, including two boys under the age of five.38 An exhaustive investigation led by Maj. Gen. Timothy McHale, who interviewed more than 50 witnesses, later established that not one of the victims was an “insurgent” or a “terrorist.” All were villagers, just going about their business.39 A drone crew, based at the Creech Air Force Base in Nevada, which had been tasked with protecting a foot patrol of U.S. soldiers in the area, was blamed for the mistake. Excerpts from a transcript of the conversations between Creech operators, video analysts at Air Force Special Operations headquarters in Okaloosa, Florida, and an overhead helicopter crew in Afghanistan, revealed the series of errors that led to the strike: “The [military-aged male] that just mounted the back of the [Toyota] Hilux had a possible weapon, read back possible rifle.” “Be advised there was a brief scuffle, looks to be potential use of human shields, but definite suspicious movement, and definite tactical movement.” “Be advised, our screener just called one [military aged male] near the SUV, appears to be holding a weapon.” “Our screener just called out one additional weapon. Was laying on the ground, where praying, picked it up and now has entered the truck.” About 20 minutes after the missiles had been fired, the chat transcript reveals that the soldiers realized that not only was the video feed too pixelated for them to identify women and children, the weapons call was also wrong. “The thing is, nobody ran.” <“Yeah, that was weird.” “Uh, have you been able to positively identify any individuals with weapons at this point?” “Yeah, there’s definitely no weapons on the guys in the middle vehicle.” “Let’s keep looking at whatever.” “We looked at all of them and I don’t think that any of them have weapons.” “They’re trying to surrender, I think.” “I personally wouldn’t be comfortable shooting at these people.” “Believe possibly two of those, maybe 3, were female. They wore bright colored clothing.” “He’s calling females? They said 21 males, no females.” “Dude, we watched these guys stop multiple times and every time they were all wearing all black and only afterwards did we ever see any color.” “It’s possible the…the women and children never got out of the car, at the stops.” “Be advised we do have what looks to be 3 women and 2 children possibly trying to surrender.”

|

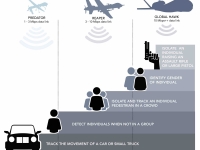

The quality of a full-motion video camera’s imagery can be determined by the Video-NIIRS rating (V-NIIRS) of the feed. The standard is based on the National Imagery Interpretability Rating Scale (NIIRS) which assesses the clarity of still photography.32

With a V-NIIRS rating of 5, the Versatron cameras on the original MTS-A sensor carried by the first Predators could watch over troops in a vehicle, but definitely not identify them, even by their uniforms.

An image with a V-NIIRS rating of 6 has the potential to find an individual who is isolated, but not one in a crowd. A V-NIIRS-7 allows an observer to track an individual wandering through a crowded market; V-NIIRS-7.5 can capture simple hand movements like picking up a mobile phone. V-NIIRS-8 is required to positively identify a man from a woman or child. An image rated at V-NIIRS-8.5 is needed to track a person firing an assault rifle, but still would not be able to identify someone using a small pistol.

These numbers explain why imagery analysts see individuals as “blobs.” Notably only the MX-20 or MTS-B ball, carried by newer Reapers and piloted surveillance aircraft, approach the quality to identify men from women.33

One of the major reasons that drones carry such low resolution video cameras is the limit in the amount of data a drone can transmit in real time to overhead satellites. Predators initially fielded modems that broadcast at 1-3 megabits per second (Mbps), and Reapers no more than 10 Mbps. (see “Relaying the Data “section). Even using the Reaper’s high rate, an imagery analyst cannot identify a person’s distinguishing facial features.

Location Data

While most discussions of drone footage tend to focus on quality and detail, those are not the only critical factors. Archival video, which analysts need to determine patterns of life (especially since the operators work in shifts), needs to have precise location data. To that end, drones transmit a code alongside the image.

For analog video this is encoded on Line 21 of the signal (the same as closed captioning), while digital video carries a KLV (Key-Length-Value) code. Since the analysts need to be able to compare video footage, the Line 21 code from analog video is supposed to be converted into KLV codes at a ground station. But this transformation often fails.34

What that means, in plain English, is that location details for older Predator video feeds have often been lost. Recently, the Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA) became concerned that the video metadata was often discovered to have “incorrect values, missing keys, and corrupted data.”

To determine the prevalence of this problem, DISA conducted an experiment to archive and study a week’s worth of data from 80 surveillance aircraft, many of which were drones, operated by the Pentagon in mid-March 2013.35

The results showed that only two out of three aircraft were able to provide location data. In addition, the quality of their data varied wildly: Predators and Reapers using analog video only provided complete data once every 2-4 seconds, or roughly one percent of location data transmitted by the more advanced piloted reconnaissance aircraft, which recorded their location 30 times a second.

There is another problem with location data from drones—a phenomenon known as “inherent error” that stems from a variety of factors such as drift and ionospheric effects. These can cause measurements to be inaccurate by as much as 20 meters, unless the system is calibrated and controlled by a skilled operator.36

While the use of landmarks and imagery databases can often help correct these machine errors, the system is by no means perfect. “Imagery analysis is time and resource intensive. Rectification, georectification, and orthorectification operations must be performed by a trained specialist on unique equipment with purposeful access to updated reference imagery databases,” writes Marine Capt. Patrick Coffman in his 2015 thesis for a master’s degree in Information Warfare Systems Engineering. “If any of these components is missing, the procedure cannot be completed.”

Coffman described a Marine Special Forces operation in western Afghanistan where 30 analysts had to be brought in to accurately identify a single target in a two-block urban environment. “Why is it so difficult to exploit motion imagery derived from UAVs?” he asked rhetorically in his thesis. “Why does it take special equipment and training to do what Google Earth can in my living room? In the most technologically advanced military this world has seen, this operational restriction is nearly laughable, if not utterly frustrating.”37

Of course, the video camera is only one of the sensors on a drone. Far more important are the devices used to “geolocate” mobile phones. We’ll get to that after we discuss the other visual sensors available to drone analysts: infrared technology, thermal imagery and radar tracking systems.

< Previous • Report Index • Download Report • FAQ/Press Materials • Watch Video • Next >