Sweet and Sour

Coca-Cola is indirectly benefiting from the use of child labor in sugarcane fields in El Salvador, according to a new report by Human Rights Watch (HRW), which is calling on the company to take more responsibility to ensure that such abuses are halted.

Between 5,000 and 30,000 Salvadoran children, some as young as 8 years old, are working in El Salvador's sugarcane plantations where injuries, particularly severe cuts and gashes, are common, according to the 139-page report, 'Turning a Blind Eye: Hazardous Labor in El Salvador's Sugarcane Cultivation.'

Since the 1950s, sugar production has grown in importance in El Salvador since the 1950s, and by 1971 it exceeded the production of basic grains. By the 1990s, sugar, which was produced mainly by state-owned plantations, had become El Salvador's second-largest export crop after coffee. Beginning in 1995, most of the plantations were privatized.

While Coca-Cola does not own or buy cane directly from any of these plantations, its local bottler buys sugar from El Salvador's largest refinery, Central Izalco, and distributes the soft drink throughout Central America. HRW found that Izalco purchased sugarcane from at least four plantations that use child labor in violation of the law.

Coca-Cola denied any connection with child labor in El Salvador. "Our review has revealed that none of the four cooperatives identified by HRW supplied any products directly to the Coca-Cola Company, and that neither the Company nor the Salvadoran bottler have any commercial contracts with these farm cooperatives," Coca-Cola officials said in a statement released in response to the report. The company publicly opposes the use of child labor, and its "Supplier Guiding Principles" program provides that its direct suppliers "will not use child labor as defined by local law."

Michael Bochenek, counsel to HRW's Children's Rights Division, believes the company should take more responsibility. "Coke is saying that it has no responsibility to look beyond their direct suppliers, and we disagree," he said. "If Coca-Cola is serious about avoiding complicity in the use of hazardous child labor, the company should recognize its responsibility to ensure that respect for human rights extend down the supply chain."

Under Salvadoran law, 18 is the minimum age for dangerous work, and many consider work on the sugar fields to be one of the most dangerous jobs in agriculture. (Age 14 is the minimum for most other kinds of work in El Salvador.) But the relevant provisions are not generally enforced, in part because the children are hired as "helpers" and are therefore not afforded the same protections as employees.

Children hired as helpers often must pay for their own medical treatment if they are injured in the fields, despite a provision in the labor code that makes employers responsible for medical expenses for injuries incurred on the job.

"Child labor is rampant on El Salvador's sugarcane plantations," said Bochenek, lead author of the HRW report, which was based on interviews conducted early last year with 32 children and youths between the ages of 12 and 22, as well as with parents, teachers, activists, academics, lawyers, government officials, and representatives of the Salvadoran Sugar Association. "Companies that buy or use Salvadoran sugar should realize that fact and take responsibility for doing something about it."

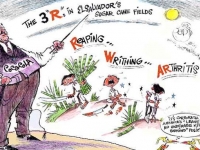

Cutting sugar cane is back-breaking and hazardous work for a variety of reasons. The most common tools are machetes and knives. Both the monotony of the work and the fact that it is usually performed under direct sunlight make for frequent accidents, even among experienced workers.

Virtually all of the children interviewed by HRW bore multiple scars from cuts they received during their work. ''I cut myself on the leg,� one 13-year-old boy told an HRW interviewer as he displayed a scar on his left shin. �There was a lot of blood. I got stitches at the clinic.� His mother added that the incident occurred when he was 12.

Because cane is often burned before it is cut to clear away the leaves, workers may suffer smoke inhalation and burns on their feet. As one former labor inspector told HRW, "Sugarcane has the most risks. It's indisputable - sugarcane is the most dangerous (agricultural work)."

Although not as hazardous, planting sugar cane�work that in El Salvador is mostly performed by women and girls�is also difficult and exhausting. Working under the hot sun, planters must keep up with tractors that plough rows for the cane.

Children who work on sugarcane plantations, particularly during the harvest, are often required to miss the first several months of school each year, while older children often drop out of school entirely.

HRW recommends that Coca-Cola and other businesses buying Salvadoran sugar require their suppliers to incorporate international child-labor standards in their contracts with the plantations and adopt effective monitoring systems to verify that compliance.

But it should not be a matter of simply firing child workers, particularly when their families have come to depend on the extra income their children bring home, according to Bochenek. ''What is really needed to ensure that child labor is addressed in a comprehensive way is one that combines educational incentives and other safety nets," he said. "It's fine to have a carrot-and-stick approach if the stick is the last resort." He cited programs in Mexico and Brazil that provide cash grants to parents for enrolling their children in schools instead of sending them to work.

The sugar industry association in El Salvador has begun to work with the International Labour Organisation (ILO) on a more comprehensive approach to the problem of child labor, which HRW sees as potentially helpful.

In its reaction to the HRW report, Coca-Cola officials also noted that the sugar industry has been meeting with cooperatives to emphasize its "zero tolerance" for child labor. The company promised to step up its own monitoring and enforcement activities and to "continue to help provide increased educational opportunities for children from the farm cooperatives."

Company officials added that they will "work with our direct supplier to help (it) strengthen (its) outreach programs (and) will also work with the sugar industry association as they continue to implement a major program with the ILO to help families involved in Salvadoran sugarcane cultivation."

"That's awfully short on specifics," said Bochenek, who called for the company to make concrete commitments to finance and support educational and related programs and to assume greater responsibility for their success.

"Where you have had a company that used sugar, which it knows is produced by child labor, it can support these programs by contributing financially and in terms of technical assistance in concrete ways, as opposed to just saying the right thing," he said.

The new report marks the latest in a growing number of efforts by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to press multinational corporations to take more responsibility for labor conditions under which their products, or components of their products, are produced.

Under pressure from NGOs, for example, major chocolate manufacturers agreed last year to take part in a program to monitor West African cocoa plantations to ensure their compliance with minimum international child labor standards. Initially, the chocolate manufacturers insisted that they bore no responsibility for abusive practices because they bought beans from commodity brokers, not from the farmers themselves. But as NGOs increased pressure, the chocolate manufacturers agreed to participate in the monitoring program.