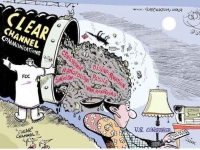

Clear Channel Rewrites Rules of Radio Broadcasting

Against a backdrop of red, white and blue curtains, emblazoned with the words of the constitution of the United States, the heads of some of the world's biggest radio companies gathered for the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) annual meeting last week in Philadelphia, at the Pennsylvania Convention Center.

The exhibition floor was crowded with curious delegates playing with new gadgets, surrounded by cool blue lights. One booth gave away free radios to promote Family Net, an internet service that filters out pornography, while the United States Air Force had a sports utility vehicle on display, loaded with state-of-the-art flat television screens, DVD players and 12 booming speakers, to convince broadcasters to play recruitment advertisements for the military.

What was probably most unusual on the exhibition floor was the absence of the biggest radio company in the country: Clear Channel. Although the company is not a household name, most radio listeners in the nation have heard the company's music.

Clear Channel is a product of the deregulation of radio in the United States through the Telecommunication Act of 1996, which overturned the rule limiting to forty the number of radio stations around the country that a single company could own.

Today Clear Channel owns over 1,200 stations, or roughly one in every ten in the country, over 776,000 outdoor advertising displays, such as billboards and street benches, as well as 200 major concert halls across the nation. The company represents the biggest and most profitable bands and stars in the business, ranging from N'Sync, Tina Turner and Pearl Jam to sports legends like Michael Jordan and Andre Agassi.

But by no means did the company boycott the convention. John Hogan, the president of Clear Channel radio and his rival Joel Hollander, president of Infinity, were available to meet attendees who had paid up to $895 to attend the gathering, at a special "super session."

Hogan told his audience that the radio multinational was there to provide consumers with what they wanted. "It is really the audience that is the litmus test. I have certain opinions and political beliefs. It shouldn't be up to me, it is up to the community," he said.

Not every member of the audience at the super session agreed with Clear Channel's philosophy. Patrick Clawson, a local reporter, stood up to challenge Hogan.

"Since Clear Channel came into our community and consolidated the stations there, and began to take up a wide share of revenue from that market, Clear Channel has eliminated entirely the local news department from those stations. Clear Channel now broadcasts news that originates from Baltimore over 100 miles away, and that centralized news agency has never had a reporter in our community," he said.

"We had a industrial plant accident in our area not long ago, where the plant manager called the stations at about 3 o'clock in the morning because they need to get the word out to tell the community about the accident and also to advise the employees not to come into work, but he was greeted with an employee [of Clear Channel] who said: 'Sorry, all our programs are delivered by satellite, and we can't anything on air until six in the morning.' With the elimination of local programming, how does this method of operation serve the public interest?" added Clawson.

Hogan declined to reply to the question but media activists, who attended the convention were eager to explain: "The problem with Clear Channel having so much market power is that they start to be able to control the outcomes of the competition that they are in," says Pete Tridish, founder of the Philadelphia-based Prometheus Radio Project, which supports community FM stations around the world.

"When you have a company that not only owns one radio station but eight radio stations in one town plus all the billboards and all the concert venues, and all the promotion machinery, suddenly they have a level of power that their competitors have no way to compete with. Once their competitor are out of business they have free reign to do just about anything that they please, that is the same just as any other other monopoly."

Indeed Hogan's comments also contradicted the opinions of Lowry Mays, the founder of Clear Channel: "If anyone said we were in the radio business, it wouldn't be someone from our company. We're not in the business of providing news and information. We're not in the business of providing well-researched music. We're simply in the business of selling our customers products."

Yet when radio began in this country, it was not supposed to simply be a commodity. The Federal Communication Commission, a government federal agency that was established by the Communications Act of 1934, was charged with allocating spectrum space to maximize "the public interest and to encourage a diversity of voices so as to promote a vibrant democracy."

Over the years this original mission has largely been forgotten, says Norman Solomon, the executive director of Institute for Public Accuracy. "The FCC has functioned much more as a lap dog to the media industry than any kind of watch dog on behalf of the public to further deregulate and further hijack the public airwaves for private profit."

Clear Channel has gone beyond just axing news. Many believe that the company fires anyone with political opinions other than their own such as Davey D, the host of a popular talk radio show on KMEL, a black-owned station in Oakland, California, that launched the careers of rappers like Tupac Shakur and MC Hammer.

In October 2001 when the United States was on the verge of launching its invasion of Afghanistan, Davey D broadcast an interview with Barbara Lee, the only member of the United States Congress to vote against the war.

KMEL, which had recently been bought by Clear Channel, heard about the show and promptly fired him. Meanwhile company executives sent a memo round to its stations at about the same time warning them not to play any peace songs such as John Lennon's "Imagine" or music by the band Rage Against the Machine.

On the other hand, Clear Channel has not been opposed to all forms of political organizing. In 2003 the company paid for pro-war rallies around the country to support the invasion of Iraq as well as for a 33,000-pound tractor to smash a collection of Dixie Chicks CDs, tapes and other paraphernalia, at an event in Louisiana, because the bands had the arrogance to protest against the war.

Today the rules of media ownership that spawned Clear Channel have been further loosened. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC)), which is led by Michael Powell, none other than the son of United States secretary of state, Colin Powell, voted in June to allow companies to buy more television stations and own newspapers as well as broadcast outlets in the same city.

Critics include consumer advocates, civil rights and religious groups, small broadcasters, writers, musicians, academicians and the National Rifle Association. They say most people still get news mainly from television and newspapers, and combining the two is dangerous because those entities will not monitor each other and provide differing opinions.

Promotheus has been one of the leading advocates seeking to block the new ruling. A month ago the organization persuaded a federal court in Philadelphia to temporarily block the new FCC rules.

The delay will give Prometheus Radio Project time to argue that the new regulations decrease the public's ability to get on the air, a difficulty apparent in Philadelphia, which has no public access radio or television.

Meanwhile local broadcasters are starting to get worried about added multinational competition as a result of yet another set of proposed new rules that would allow national satellite radio channels like XM and Sirius to broadcast in local markets by inserting "local" weather reports from their national headquarters.

But Edward Fritt's, NAB president offered some support to the local radio stations, which he said provided important public services.

"Think back to the blackout that paralyzed much of the Northeast and Midwest. Huddled masses in New York gathered around battery-operated or car radios to find out whether they'd been victimized by another terrorist attack.

And then -- Hurricane Isabel, just a few weeks ago. Many radio stations blew out commercials for wall-to-wall coverage of the storm. I can assure you, there weren't many people in Isabel's path who tuned to satellite radio for storm-tracking information," he said.

"We're not against competition. But satellite radio was authorized as a national programming service only! It is past time for the FCC to issue a final rule barring satellite radio companies from delivering locally originated programming."

Listen to the audio version of this story on Free Speech Radio News

Dante Toza is a Correspondent with Free Speech Radio News