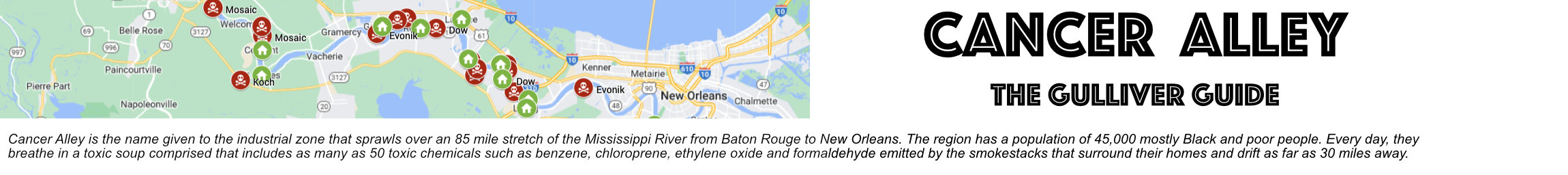

Cancer Alley: Denka profile

Denka is a chemical company headquartered in Tokyo, Japan. Founded in 1912 in Hokkaido, it is the world’s largest manufacturer of neoprene,* which is used to make a variety of products such as adhesives, beer cozys, gaskets hoses and wetsuits. It also makes cement and plastics like styrene.

The company’s most controversial asset is a neoprene factory named the Pontchartrain Works facility, built by Dupont in 1968 in the town of Reserve, St. John the Baptist parish, Louisiana. The U.S. National Air Toxics Assessment found that cancer risks around the plant were as high as 1,505-in-1 million, 50 times higher than the national average. In a one mile radius around the plant, the population is 94 percent Black.

While there are three other major polluting factories close to the Denka plant (Dow St. Charles Operations, Evonik Industries and Marathon Petroleum) a report from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), published in May 2021, makes it clear that Pontchartrain Works is the major problem. “The individual lifetime cancer risks in the census tracts with elevated cancer risks in the remaining metropolitan area are driven by chloroprene emissions from the Denka facility,” the reports says.

“It’s time for EPA to use the full extent of its authority to reduce chloroprene and ethylene oxide emissions in St. John, as well as strengthen national protection – and stop cutting corners on public health," Emma Cheuse of the NGO Earthjustice, the lawyer for the Concerned Citizens of St. John, said in a press release after the EPA report was issued.

“The high cancer rates in St. John the Baptist Parish are an emblematic example of environmental racism,” said Maryum Jordan, a lawyer with the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law in Washington DC. “The communities affected by the Denka facility would greatly benefit from comprehensive, protective air regulations.”

(See the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's Enforcement and Compliance History Online for Denka's plant in Reserve. Note that auto-display of data from this link may be disabled for some browsers. If so, copy the URL manually into a new browser window to see it.)

"It is difficult to describe the effect their pollution has had on me and my family. In one word, it is horrible. I look at my poor daughter now, ill with a rare intestinal disease linked with chloroprene exposure," Robert Taylor, a local resident wrote in the Guardian newspaper. "I think also about my neighbours, aunts and brothers – because these people can’t move. Forced to live there and breathe this poison so these companies can make maximum profit. All my community has ever asked if for is basic safety and decency to preserve our health and the air we breathe."

In June 2020, Denka issued a press release that stated: “DPE operates in compliance with legally mandated chloroprene monomer emission standards, and has achieved significant reductions in emissions of this substance as part of its efforts to be a good neighbor in the local community.” (DPE stands for Denka Performance Elastomer, the U.S. subsidiary of Denka Japan)

“In addition, DPE has submitted a formal request to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to revise its toxicity assessment of the substance, and it is expected that the assessment method submitted by DPE will be accepted and verified by the EPA.”

While the company response was technically correct, it appears to have conveniently side-stepped reality.

Denka did install new air cleaning equipment - a regenerative thermal oxidizer - in 2014 that supposedly reduced chloroprene emissions from the factory by 85 percent.

But in 2020, the actual measured concentrations of chloroprene by the EPA shows that the actual levels of chloroprene in the local air have not fallen anything close to necessary. Indeed in years of monitoring, the Denka plant has rarely been able to record levels below the permitted amount, established by the EPA, which is 0.2 micrograms per cubic meter, which is associated with a cancer risk of one in 10,000 people. (The EPA “preferable” emissions level is 0.002 micrograms per cubic meter which is associated with a cancer risk of one in a million people.)

Indeed, air monitoring data recorded by the EPA, showed that levels at 238 Chad Baker street, about a mile from the Denka plant, was as high as 16 micrograms per cubic meter on September 9, 2020, 80 times higher than the maximum allowed. (The peak concentration recorded at the same location was 47.8 on June 28, 2018 or a staggering 23,900 times higher than the preferable limit)

Community members say Denka likely knew that it would never meet the government requirements. “At the same time they’re saying they’re going to reduce by 85 percent, they were lobbying the EPA to raise the emissions level,” Patrick Sanders, a St. John Parish School Board member, told the Advocate newspaper.

Denka hired Ramboll Environ, an industry-consulting group, to produce a report that claimed that EPA’s ‘inhalation unit risk’ levels for chloroprene were 156 times too high and request a change. Freedom of Information request show that Denka and Ramboll met with EPA officials multiple times between July 2018 and December 2020 in an effort to change the standards.

In order to settle this matter, EPA hired Versar, an independent consultant, to conduct an external review of the proposed change with the help of nine outside experts. The final reports, published on December 17, 2020, recommended that the agency be wary of the Denka proposal.

“My general impression was that Ramboll/Denka had dismissed or ignored some of the available science and chose a simplistic approach,” wrote Raymond Yang, professor emeritus of Toxicology and Cancer Biology at Colorado State University, one of the experts. “The Ramboll/Denka application is not scientifically strong enough, at this time, to support their petition.”

On March 1, 2021, Denka quietly withdrew its formal request for the EPA to lower the toxicity assessment of chloroprene when it became obvious that EPA was unlikely to grant it.

While local residents blame Denka for the pollution, they also blame EPA for not doing enough.

“Our families are dying of cancer because for the last four years EPA has ignored our community and allowed companies like Denka to dump hazardous pollution into our air,” Mary Hampton from the Concerned Citizens of St. John, said in a May 2021 press release issued by Earthjustice. “EPA had a plan in 2016 but never followed through to protect us. EPA must fix this environmental injustice now.”

An internal investigation by Sean O’Donnell, the EPA’s own inspector general, supports the community’s charge that the agency is not doing enough. O’Donnell sent a formal report to Joseph Goffman, who runs the EPA’s Office of Air and Radiation, on May 6, 2021, recommending that the agency conduct new residual risk and technology review of the Denka factory to protect community health.

However, the EPA continues to drag its feet. Agency officials told the inspector general’s office that they had no plans to conduct a review “because [EPA] does not want to expend rulemaking resources on a technology review covering one facility—Denka. Furthermore, the Agency believed that emission reductions could be achieved more quickly by working with the state and the facility.”

The activists disagree.

“EPA has long known that St. John residents face unacceptable cancer threats from breathing industrial fumes every day, yet for years EPA has failed to fulfill its basic responsibility," Emma Cheuse of Earthjustice, the lawyer for the Concerned Citizens, said in the NGO press release. “It’s essential for EPA to listen to the community of St. John and show that the new leadership will no longer sweep community health emergencies under the rug."

Outside Cancer Alley

In Japan, the company has a major presence in the town of Omi in Niigata prefecture where it has a neoprene factory, cement plant and a hydroelectric plant. A worker was killed in a heat blast from an electric furnace at the Omi plant in Niigata in 2013, and another worker died at the Ōmuta plant in Fukuoka prefecture in 2018 after the collapse of raw material bulk bags. A distillation tower at the Denka styrene factory in Chiba prefecture also caught fire in 2018 as it was being demolished.

*in 2022

To learn more about Denka, see the CorpWatch Gulliver profile here. A complete list of CorpWatch's Cancer Alley profiles may be accessed here.

Quick Facts: Denka

Environmental justice indicators within a one mile radius of Ponchartrain Works plant in Reserve (US EPA, 2022)

|