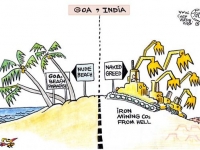

Goa Cursed By Its Mineral Wealth

Set on India's west coast, Goa is renowned as a beach paradise popular with Indian and foreign tourists alike. Just a few miles inland from the quaint restaurants and the pristine waves lapping the silver shores of India's smallest state, iron-ore mining is destroying the environment, say activists and locals.

Shirgao is just one of many North Goan villages feeling the effects of the boom in iron ore mining since 2000. "The mining companies have mined below the water table and destroyed all our water sources," says Francis Fernandes* (not his real name), 55, a resident of the village. "In our village, people are dependent on the paddy fields for earning a living. But for the past seven years, they haven't been able to cultivate their fields as there are no longer any irrigation facilities. Traditional occupations are being destroyed. People are also suffering from tuberculosis and other diseases [worsened or] caused by pollution. We're living a miserable life now."

The landscape around Fernandes's village is scarred by vast mines, dug deep into the rich red earth. The companies operating there include two of the largest iron ore mining operators in the state - Dempo Mining and the Chowgules Group.

The state accounts for more than 30 percent of India's iron-ore exports, according to export figures from 2008. Industry profits flow to the federal government and more than 100 mining companies in the state, many of which are small-scale privately owned operators. The largest mining company in Goa is Sesa Goa, a subsidiary of the British-based Vedanta Resources. Sesa Goa exported 4 million tons of iron ore in 2008 and reported post-tax profits of US $296,178,660. Other major players in the industry include Dempo Mining, Sociedade de Fomento, the Chowgules Group and Salgaocar Mining Industries. All these companies have their head offices in Goa.

Between 2002 and 2007 they and the smaller players helped double Goa's iron ore exports to almost 40 million tons per year. The boom was spurred primarily by increased demand from China's steel industry. That all of Goa's iron ore is exported abroad further galls environmentalists, who bolster their call for the mines to be closed by charging that their state is being destroyed to develop China's economy.

Indeed, the iron ore industry that brings riches to the federal government and to mining companies accounts for less than 1 percent of Goa's total revenues. Activists and industry critics say that the mining companies are not giving enough back to the state and to people like Fernandes.

One problem is a royalty system under which Goa and other iron-rich states receive a fixed rate of between $.08 and $.52 per ton, depending on the grade of the ore. This system ensures that India's iron is among the cheapest in the world, since most countries use an ad valorem evaluation (a proportion of the value of the good) that adjusts with the international market price.

Mineral-rich states such as Goa estimate that they would double their earnings from mining if India switched to an adjustable system. "The royalties are completely arbitrary," says Ritwick Dutta, a leading environmental lawyer and founder of the Delhi-based Environmental Impact Assessment Resource and Response Center (ERC). "How do you arrive at that figure? Environmental and social impacts are not factored in at all."

Revenues to the states are further diminished by allowing the industry to self-report production levels, thus presenting companies with ample opportunity to under-declare in order to increase profits. Sujay Gupta, vice president of communications for one of Goa's largest mining companies, Sociedade de Fomento, confirms that abuses occur, but says they are confined to companies recently established to cash in on the iron ore boom.

"The fly-by-night operators are simply stealing. A lot more [iron ore] is being mined than is being declared," he says.

The Goa mining department is "currently examining these claims and looking for ways to clamp down on illegal activity," says Shri A. T. D'Souza, senior geologist at the mining division of the Goa state government.

Companies such as the Resourceful Group, which operates a mine in the Sanguem area of South Goa, defend the industry as the "backbone of Goa's economy," noting that mining employs 11,000 people directly and a similar number indirectly, through transport of the ore. But most of these employees are migrant laborers from states such as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, with high levels of poverty and unemployment.

"In Goa, it is not the industry which determines lifestyles but lifestyles that determine the industry," says Dr. Claude Alvares, director of the Goa Foundation, a 20-year-old environmental organization. "Goans will take time off for religious festivals and other occasions. So mining companies want to employ non-Goans who will be a more dependable source of labor."

Environmental Impacts

While financial benefits to Goa and its people are limited, damages to the environment are extensive.

The Goa Foundation says that mining has caused far more destruction to Goa's eco-system than all other economic activities in the state, including tourism and chemical factories.

The commonly used practice of "open cast" mining creates up to 3 tons of waste for each ton of ore produced. This waste pollutes rivers and lakes - many of which run red with ore. Mining practices also pollute the land, disrupting animal life and flowing onto farms and damaging land fertility. Large dumps of earth dislodged by mining litter the landscape.

Gupta admits that the environment is being hurt, but again, blames the newcomers who arrived after the boom. "Because of the sheer number of players - and the quantity of mining going on - damage has been caused to the environment and pressure increased on the water table. A great deal of work is needed to improve the sustainability of mining in Goa."

The environmental impact is exacerbated by the coincidence of India's iron ore belt with the Western Ghats, a fragile eco-system ranked as one of the world's 12 ecological hotspots. Rich in biological diversity of plant and animal life, the highland area stretches 1,600 kilometers, running just inland along the length of India's west coast, through the states of Goa, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala.

The effects of mining in the state go beyond the direct pollution released. The industry is also taking a toll on infrastructure, air quality and public safety. Every day, up to 12,000 trucks race to and from the mines and Goa's main port, Marmugao, spreading dust and exhaust fumes. Although the maximum legal load is 10 tons per truck, most vehicles are overloaded, carrying 15 or 16 tons, and damaging Goa's narrow roads. With the drivers paid per load, they need to pack in as many trips as they can per day and have little incentive to drive slowly and with care. "There are many accidents because of the trucks," Anthony Da Silva told an anti-mining rally in Goa in February 2009.

Some activists are calling for a cessation of mining activities until environmental concerns are addressed. "Is it really feasible to stop mining?" Gupta asks. "Mining takes place in all countries. There is a huge demand for steel and this is met by mining iron ore. The arguments against mining are flawed. Instead there should be a strong demand for sustainable mining."

Responding to charges that the industry is doing too little to protect the environment, D'Souza, from the Goa government mining division, asks: "How much is enough? With open-cast mining there is always some damage caused."

Water becoming Scarce

Activists are warning that "some" environmental damage to farms, forests and water resources has already become irreversible. Fear for the future and already visible destruction have sparked public unrest.

"It's a matter of survival for the state," says local activist, Sebastian Rodriques. "We're heading for all-round destruction - a major catastrophe in the next decade." Sociedade de Fomento is currently suing the well-known activist for defamation.

"The situation will definitely get worse over the next five years, particularly as far as water supply is concerned," warns Ramesh Gaunes, a teacher from Bicholim in North Goa, who has been campaigning against environmental abuses by the mining industry for a number of years.

Many activists are focusing on the vulnerability of water supplies in the region, despite its vast network of rivers and lakes. Some communities have been left without unpolluted water, and in many villages, including Pisfurlem and Shirgao in North Goa and Muscauvrem in South Goa, water sources have dried up almost completely.

These communities must now rely on mining companies to truck in water. "We used to have tap water in our village," explains Fernandes from Shirgao village, "but now water is in very short supply. Occasionally the companies bring us water, for example during festival times, but only because the government tells them to. Most of the time we are struggling with little water."

"Once you destroy the groundwater systems, you have to bring in tankers to provide water. What will happen to these communities when the mining companies stop bringing the tankers?" asks Dr. Claude Alvares, director of the Goa Foundation.

That day is coming. Mine owners have predicted that ore reserves will be exhausted in 10 to 20 years and the companies will then decamp, leaving communities high and dry.

Token CSR Projects

"People are making huge profits at our expense," D'Silva told the crowd at a February anti-mining rally in Goa.

The companies, however, say they are giving back to the communities in terms of social and environmental projects. In 2000 some 14 Goan mining companies established the Mineral Foundation of Goa to implement corporate social responsibility (CSR) schemes in mining-affected communities. "In the beginning, it was mostly charity work we did," explains the foundation's executive director Swaminathan Shridhar. "Now we are doing CSR in the real sense."

But altruism is not the only goal. "It looks good for companies to be a member of the Mineral Foundation when they apply for their environmental clearances," Shridhar says. The foundation's total expenditure for 2007-08 was US $607,357. Although some companies also implement their own CSR projects independently of the foundation, this budget is a pittance compared to their huge profits. The two largest companies - Sesa Goa and Dempo Mining - alone report combined post-tax profits of over $530 million per year.

The quality of some CSR projects has also raised questions. While some education and health projects have benefited local communities, other schemes, such as paying women US$2 per day to sweep the dust from the streets after trucks pass, are generally regarded as a waste of time and resources, and are simply out of touch with community needs. In Shirgao village, where livelihoods have been badly affected by the mining, "The companies have done nothing for us," Fernandes says. "They haven't provided any schools or hospitals in our village."

Some companies counter that their ability to do good is hampered by environmental activists and community organizations that refuse to work with them to improve the situation. "We're reaching out to the anti-mining activists, but they are not willing to engage with us" says Gupta of Sociedade de Fomento.

But while the pace of reform is slow, iron mining is expanding. According to the Center for Science and Environment, a Delhi-based research and advocacy organisation, 8 percent of the state is already under mining. And if all applications for leases currently pending are cleared, more than 25 percent of this paradise state will become vulnerable to the environmental devastation already wrought.

It seems that Goa, blessed by fertile land and sparkling beaches, is cursed by its mineral wealth. "Now the mining has destroyed our water supply, people are trying to leave the village. But it's difficult - these are poor people, dependent on the land for making a living," says Fernandes.

- 104 Globalization

- 116 Human Rights

- 182 Health

- 183 Environment

- 208 Regulation